Service Stories told by our Veterans in their own words.

Please scroll down and up to view the entire page.

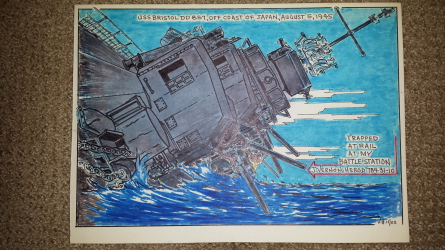

J. VERNON HEROD

From Oak Ridge to Hiroshima

December 7, 1941 to August 6, 1945

This story begins early the morning of December 7, 1941 at my mother’s old home place near the future site of what would become The Atomic City, the day Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

This story ends early in the morning on August 6, 1945 near Hiroshima off the coast of Japan, the day the United States bombed Hiroshima.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor was done during my family reunion near Oak Ridge, TN.

The bombing of Hiroshima was done as my ship reunites with the 3rd Fleet near Hiroshima, Japan.

OAK RIDGE, TN, the Atomic Bomb City, sprang up during World War II as the largest center of atomic-bomb production in the United States. Its existence was not officially known until President Harry S. Truman announced production of the atomic bomb in August 1945.

HIROSHIMA is the Japanese city on which the first atomic wartime-bomb was dropped. On August 6, 1945, a United States Army plane dropped a single atomic bomb on the center of the city destroying about 60 per cent of Hiroshima and killing about 80,000 people. An even greater number were wounded or have been missing since the attack and an undetermined number of victims died of the effects of atomic radiation.

----

On December 7, 1941, our family was having a reunion near the future site of what would become Oak Ridge, the Atomic City. Many of our family present that day would be future employees in helping to produce the atomic bomb that would fall on Hiroshima August 6, 1945.

When our family heard the news of the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, we were devastated. In our family there were nine children with the five of us boys being the younger. As young as we were, there was no doubt that all five of us would serve in the military.

I joined the Navy shortly before turning 18 and was assigned to the 3rd fleet which was shipped out to the South Pacific.

This had been a bloody war, and from day to day we would see many of our large B-29s fly over as they were on their way to various targets over Japan. I had suffered the loss of more than eleven close neighborhood friends in this conflict. Some perished in various military engagements around the world even before I shipped out for the Pacific. Just a short distance from us, Robert Crane, a childhood neighbor and playmate, perished along with many other army personnel in one explosion from an enemy shell. This was only days before the war ended.

In my brief period in the combat zone many tragedies occurred. Witnessing mid-air collisions while aircraft were crashing into the sea became an every day experience. Men were dying daily and we performed burial at sea ceremonies.

On August 5th, 1945 we were off the coast of Japan blowing up mines in preparation for the final assault. Our large battlewagons were actually shelling targets on the shore fifteen miles away, while many projectiles were landing about twelve miles beyond the shoreline.

While engaged in clearing the waters for the invasion, our ship was involved in a collision with a heavy oil tanker. As we crashed into the side of the heavily loaded tanker, much of our bow disintegrated as we penetrated its structure. We became trapped as the tremendous force submerged us into the sea. With three gigantic thrusts we would be gone; the first one had already occurred.

The crew began running to their positions on deck. Most of the sailors fled to the stern of the ship for the most reasonable avenue of escape. I was the only one who went to the most hazardous location on board ship for abandonment. This position was on the 2nd deck forward under the heavy superstructure, and the very side that was beginning to take on water on the 1st deck.

This accident could have been very deadly if God had not intervened. On reaching my battle station to secure my life jacket I became trapped in a V position between the outside railing and the gun mount. The greater the list of the ship, the more I became trapped.

Being trapped, the only thing that I could do was just watch the water rise as it had already covered the entire port side of the 1st deck. There was the 2nd thrust, and the list became greater, and the water was rising quickly. I knew now I only had seconds of time to live. In those few seconds my entire life passed before me in review. I thought of home and my family.

Abruptly the 3rd and final thrust was felt by my whole body as the superstructure appeared to be the ceiling over my head, while the ocean was lapping at my feet. I felt there was no way out of this trap, not being able to move. The water continued to rise, and than instantly everything became pitch black as God, mama, and home came before me. In a loud proclamation I cried out, “O God!”

As soon as the word God had left my lips, there was a tremendous vibration felt all over the ship along with several violent jolts. The ship was lifted up from the water, and began to roll back and forth from starboard to port side. We were saved! Our anchor was torn lose from its resting position as it jostled into the wreckage of the oil tanker. Instantly it made connections while holding us firmly from capsizing. God was the real hero in the form of an anchor.

Our ship’s log indicated that we had exceeded the limit of 45 degrees for capsizing. The records revealed that by all means we should have gone over, possibly inflicting many deaths on the 320 man crew of the destroyer.

The miracle was discussed over and over among the crew members, but they didn’t know what God had actually performed in order to save us. I was silent while the crew was very talkative on the issue.

If you remember from the Bible how pride itself became attached to the heart of Lucifer and caused his downfall, you might understand to a degree my own connection with pride.

I was very young, and had a good job aboard ship with a good relationship with all the enlisted men as well as the officers. I did well for my early age having the rank of a petty officer. I even had men working under me, and there was no way that anyone was to know that this sailor, in leadership, could not even swim. Now you understand why they went to the safe place on the ship, they needed no life jacket, because they could swim, and I could not. This is the reason I got lost from them, and suffered this ordeal alone, except for the presence of God himself.

My life was very similar to that of Jonah in the Bible. God expected and encouraged me to serve my country, but within His guidelines. I wanted to do it, but I wanted to do it my way. As Jonah did, I kept a low profile by attempting to hide my true identity. I had the Bible with me, but it was hidden away, and was not ever consulted even while in dangerous waters.

Just like Jonah, I could not hide from God. I was fast asleep, but He sent a great wind into the sea to wake me up. Every sailor was afraid and cried every man unto his god.

God took me into the waters even as Jonah was taken into the waters. We both said, “For thou hast cast me into the deep, in the midst of the seas; and the floods compassed me about: all thy billows and thy waves passed over me.” “I cried by reason of mine affliction unto the Lord, and he heard me; out of the belly of death cried I, and thou heardest my voice.” Now, I remember how the Lord spoke to the anchor, and it delivered me out of the waters of death.

Early the next morning on August 6, 1945, the Enola Gay flew over us as it delivered the atomic bomb to Hiroshima. World War II was coming to an end.

This episode in human history, opening with the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and ending with the atomic bomb on August 6, 1945 has altered the course of mankind forever. Just as the story began with me near the very spot where the atomic bomb was to be constructed, it would end with me near the very spot where it exploded over the city of Hiroshima.

For sixty years I have kept this story mostly to myself, but have thought many times how God miraculously preserved my life. This experience developed in me a much deeper love for my country, and it also gave to me an eternal bond with my Creator that will never be dissolved.

In closing I must give a testimony for my God and my country. I love and appreciate them both, and in that order. Now I feel more ready than ever to give my life for both if and when the need might ever require it.

His own story supplied by J. Vernon Herod.

NOBLE B. VINING

EDITED TRANSCRIPT of Noble B. Vining INTERVIEW on July 22, 2014

VFW Post 1697: This is Lew Szerecz from the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 1697 in Ooltewah, Tennessee. I’m talking with one of the members of our Post, Noble B. Vining. He has a fantastic service story and we’re getting ready to talk and, hopefully, transcribe what he says and then put it on the Web with some photographs. So, go right ahead, Mr. Vining.

Part One: Induction and Training

Noble B. Vining: As I grew up I never thought that I’d ever end up in the Armed Forces. I had no idea of it, but in 1940 I was to begin my senior year at Andrews University, and it was in September of that year that they had the first draft and it so happened my birthday came early in the month so I was eligible. They were drafting twenty-one year old singles, as I remember.

Well, that’s okay, but then when they drew the first numbers out of the bag to see who would go in first, would you believe that I was in the batch that was supposed to go in at the end of November and that was in the beginning of my senior year? And so it was not necessary, I mean we were not at war, so it wasn’t any problem to get deferred at that time. So I was deferred, I was going to be a summer school graduate, which would take me into the ’40-’41 school year and I would get through in September of ’41.

Andrews University was in Michigan, and I was at the draft board in Berrien Springs and so when I graduated I had to transfer my registration back to Decatur, Georgia, a suburb of Atlanta, and when I did that I was inducted into the Army at Fort McPherson on October 16, 1941. I was there for probably about two weeks and I was sent to Camp Lee, Virginia, which was near Richmond; it was a combination medical training base and also a quartermaster. I think there were about 25,000 troops there. I went to the 6th Battalion and was in training and they picked me out because my education was in business, business administration, and I was a pretty good typist and so they sent me to clerical school and that was supposed to last two months and then basic training was going to be four months.

Well, of course, as you know, December 7 we had Pearl Harbor and I’d been out playing tennis that morning, Sunday morning, and came back to the barracks and heard all this news about Pearl Harbor. And then the next day we were ordered to go over to the parade ground, everybody in formation. We all got out there, 25,000 men. At eleven o’clock we heard [President] Roosevelt come on and declare war with Germany and Japan.

Well, of course, they decided they would cut the basic training in half; anyway, that meant that at the end of my [clerical] training it was over. I wouldn’t have to go to that other two months of basic. After he declared war, we were into the war. You know, I’ll have to admit that you wonder what’s going to happen, where you’re going to be, and where you’re going to end up. Well, about that next week I remember it was in December, it was pretty cold, and we used to go out, they would have us go out in formation before daylight in our underwear and do calisthenics. And, so we were out there doing that and it was dark, you see, except when the moon was up there and I looked up there and saw the moon and said, oh boy, at least my family and anybody else that wants to, we could see the same thing, we could see the moon wherever we are. In my thoughts I thought, well, more than that God is ever present everywhere and so I’m not going to worry about the future, I’m going to leave it in His hands. Whatever happens I’m not going to worry and so from that day to this I’ll leave it in His hands, my future. Of course, I’m getting a little old now, might not have much future left.

Anyway, on New Year’s Eve, that’ll be December 31, we shipped out on a troop train, a group of us assigned to Baer Field, Indiana, which was adjacent to Fort Wayne, Indiana. And, it was a hospital. So, I’d been training in basic as clerical work and got there. Well, it was called Baer Field, supposed to be an air base, but at that time, I think, they had a Piper Cub, maybe, in the hangar there. It wasn’t a big field. But, anyway, I worked at the hospital. I did various things and since I was a typist I always ended up with clerical work in doing that type of thing. Finally I ended up in the registrar’s office in the hospital and a bunch of pretty girls worked in there, civilians, and I was a soldier working in there, well, I don’t know, there may have been one or two of us. I thought, man, this may last a while but you know what happened?

They came in and they formed the 78th, they called it the 78th Pursuit Group and got together the cadre for that group. Now, the Army Air Forces and the Army ground forces had been separated completely, equal units but they were separate. But the Army Air Forces did not have a medical department or enlisted men. They had flight surgeons and dentists. So, anyway, they formed this medical detachment and assigned it to the 78th Fighter Group. There were probably thirty-five or forty medics in this group. So, since I was probably the only one who could type I became the clerk for that group, you see.

Well, they formed that and we were known as the 78th Pursuit Group and we didn’t have any squadrons in it, that was just it, and probably, oh, at least a thousand men in it. And we started out on a troop train from Baer Field, Indiana, and we didn’t know where we were going but we kept going west. I remember seeing the arches at St. Louis. On the way out we’d see these Army camps in different places on the railroad and we said, wouldn’t it be awful there, you know, all of them looked bad. So we kept going and finally we got out to California. On the train they put dirt, sand, on the floors of these baggage cars and had big wood stoves to cook on. And they would cook and we’d eat, you know, no air conditioning.

Well, anyway, we got out there. That evening I looked out the window and lo and behold there was a sign that said Loma Linda and that’s where the Andrews University students went to get their medical training. And there I was parked right there by the sign, it was just a little side of the road, but by the next morning we found ourselves up on the Mojave Desert. And we didn’t know what we were going to see but, anyway, we looked out the window over on the left. Way in the distance there was a camp and it had tents, pyramidal tents, you know, the four sides around the center, and they did also have tarp paper barracks and the windows were, what they used to use, chicken wire was sprayed with something so they were semi-transparent, you know, you couldn’t see. Anyway, that’s what the windows were. Well, that was the worst place we had seen.

We kept going and the train started slowing down and, lo and behold, we looked down and there was a track going back over toward this place. The train backed in there and the guys came out. They looked like this is a ranch. They said, Be sure if you’ve got any newspapers to bring them off the train, and we found out when we got there that the permanent post lived in the tents and they have a little stove in the tents. We were assigned the barracks over there. We went in covered with dust. Snakes, horned toads, I mean it was real desert stuff. So we got this barrack and cleaned it all out. It would be freezing at night and in the day time it was hot as it can be up there on the desert.

While we were there, we were there only two or three weeks but it seemed like a century. Every day they were testing P-38’s. They had not been assigned to anybody before but they were still testing them. Well, it so happened that the group before us where they were stationed, they’d had P-39’s, that’s the one with the propeller shaft going between the pilot’s legs and out through the nose to the propeller. And so, anyway, every day there would probably be a crash from a sand storm or something would happen to these P-38’s.

And, while we were there they changed the name from Pursuit Group to Fighter Group so we became the 78th Fighter Group. In addition, it was divided up into three squadrons and headquarters. And so, me being the clerk in the medical detachment the officers said, You go ahead and assign the men where you want them to the three squadrons and the headquarters. So I had the privilege, and there were two or so regular Army men in there that had been in a long time and I put one of them, the top man, he was a tech sergeant I think, of course he stayed at headquarters but the sergeant, he was a regular Army man. We had one squadron going to San Diego on the naval base. I thought that’s a good place to put him, and he was in charge of that detachment, that was 82nd Squadron.

And then I had a buddy, he was a corporal and I was a corporal. I assigned him to the 83rd, he was the head noncom, and I put myself in the 84th because I had a girl friend whose parents lived near Oakland and that squadron went to Oakland Municipal Airport, the 83rd to San Francisco Municipal Airport, the other one to San Diego.

The airport restaurant was our mess hall, but we still ate out of our mess kits and washed them the regular way and everything. One boy lived in Ohio, he did get a little pass, and the planes were still coming and going and so he walks out of the barracks where he stayed, just walks over and gets on the plane. And when he came back he got off and walked, he wasn’t probably four or five hundred yards from his bunk and he caught the plane to go home.

VFW Post 1697: You mean it was one of those fighter planes?

Noble B. Vining: No, this was an airplane, you know, a regular airplane.

VFW Post 1697: Commercial?

Noble B. Vining: Commercial airplane, they were landing there.

VFW Post 1697: In Oakland?

Noble B. Vining: In Oakland. Well, anyway, that’s just a little sidelight. When we were there about six months, we were assigned P-38’s, the first group to ever have them, the P-38 Lightning. That’s the one that had the twin fuselage, the pilot sat in a little pod in the middle. They were a little fearful of them because they didn’t know what would happen if they had to bail out because behind them was part of the tail and also they didn’t know what it would do if one of the engines failed. Some of the test pilots came up from Lockheed and put them through the paces and they landed the thing on one engine and did so much with it the [Army] pilots had confidence in it.

We patrolled the West Coast, the three squadrons did and also when convoys went out from San Francisco our planes would go as far as they could on the fuel they had and come back. We also sent some pilots and planes up to Alaska and that part of the world. In the fall we got orders to assemble at Hamilton Field which was our headquarters base. So we all assembled up there, got on a troop train and we went across the country to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey.

VFW Post 1697: What year was that?

Noble B. Vining: That was in 1942, the fall of 1942.

We were there a little bit and got orders to go aboard the Queen Elizabeth. We didn’t know what we were going on but that’s what it was. It so happened that the 78th Fighter Group was the largest group going on board at that time and our commanding officer was the commanding officer of the ship for the time being and it remained that way all the way across.

VFW Post 1697: Was it the ship or the task force?

Noble B. Vining: The ship, because he was in the largest unit he was the commanding officer of the ship.

VFW Post 1697: But he was not the captain of the ship?

Noble B. Vining: No, [only] as far as the military. We boarded the ship just as soon as it came in. We got on and we went three days and then right at the last part of the third day they started pouring troops aboard. And we had, I think, it was 12,000 on it, a huge number. They all just poured in all of a sudden.

During that three days I had the run of the ship. You know, there weren’t many on it then and up on the bow of the ship there was a huge cannon up there. It must have been, oh, 42 inches across, the diameter not the circumference; it was probably as long as from here to the end of the room there, a big thing. And it was pointed out but I couldn’t see any way for it to be adjusted to aim it. Anyway, it was there on the bow of the ship. I looked at it; it was made by the Miehle Printing Press and I had been in printing and run Miehle presses so I knew the company well. That company had their company plants in Germany, England and the United States. So I don’t know where the gun was made but I think it was originally a World War One. I never saw the guns after that; I couldn’t get up there, but they did fire it two times, not simultaneous but one day and then another day. Man, that ship just shook from one end to the other, it was such a recoil. I don’t know if they were shooting mines or what.

Anyway, we left and zigzagged across the Atlantic.

VFW Post 1697: What port did you leave from in the United States?

Noble B. Vining: New York. We went down the Hudson and out. Every seven minutes it was time. Every seven minutes it would [swerve] like that. We had some real storms and swells. A smaller ship would just ride up on a swell, but they were so big that the [Queen Elizabeth] would go up, you see, that ship would go up, I’d say, thirty degrees at least, 30-35 degrees. And because we had gotten on early I was in the bow, the front cabin in the bow, on A Deck, which was about as close as you can get to the front. We had bunks everywhere; you couldn’t even sit up in them it was so close. I would hang onto my bunk; it [the ship] would go up and come down like that. You’d hear it when it hit the bottom of the water and come down and sometimes it was up like that and seven minutes came and it would sink like that, like this. Oh, man, that was an awful feeling. You know, you were up there probably seventy feet in the air and all of a sudden it would come down like that.

Anyway, we got to England and they wouldn’t dock in Southampton, that’s where they usually would, but of course due to the war they would go north above Glasgow. We had to get off the ship onto tug boats and go on land. Got on troop trains there, went down to Glasgow, over to Edinburgh, from Edinburgh down across Scotland to England and went to Goxhill Aerodrome, it was called.

I forgot to tell you we had Thanksgiving on board the ship going over.

And, one of my duties was, we’ll bring this up. One of my duties was, the medical department has to watch out for anything having to do with the food or sanitation, anything. We ate pretty good there the first three days but the first meal after all the troops got on board, we went to the head of the lines and went to eat. And they had a dish pan, if you can imagine, it was probably about not quite two feet across, a beat up aluminum dish pan in the middle of every table. I guess that’s the way they fed the English troops. About eight of us around the table and two men would take this dish pan up to where the food was, they would fill it and they were supposed to put in that what we would eat; they didn’t want any scraps, you know. Well, I remember this particular meal was Brussels sprouts and mutton. You know, mutton is mature lamb, sheep. The two men would bring that back. Well, we had our mess kits and were supposed to have our own cutlery, so every man would dip out his stuff and we would try to eat it. And two more men were supposed to take this pan back up and wash it in, I think, it was cold water, no soap, wash that greasy pan, bring it back full of water, cold water. We were supposed to wash our mess kits in that and then two more men would take it up, dump the water and wash it out and bring it back and put it in the middle of the table and that was ready for the next feeding, you see.

Well, I went to the chief English man in charge of all that, I forget what his rank was. Of course, he didn’t know that I was just an enlisted man, so I asked him, I said, Was this the procedure, will this be the procedure for the entire time. He wouldn’t even look at me, he wouldn’t speak to me, I was just an enlisted man. You know, he didn’t talk to us. I said, Okay. So I went, got in touch with my flight surgeon and told him the situation. They were sitting up there in the officers’ mess with waitresses and courses of food, and we were sitting down there with that.

Well, I’ll tell you, they got busy and it was maybe one more meal but then they had three garbage cans with the water like they did in the Army. In one you empty your mess kit and get it clean and the next, good soapy water and then the rinse. So that’s the way it was the rest of the trip. But you know, if we’d followed that other system, it would have been, everybody would have been sick before it was over.

Then another thing was, I don’t think I mentioned they gave me the job of setting up this hospital on that ship, imagine that. Well, that was another job they gave me, put me in charge of setting up the ship’s hospital. They had the cots, nice cots and blankets and sheets and pillows and everything real nice. Of course, we didn’t have anything where we were on our bunks. But anyway, they gave me some soldiers, they weren’t medics, it didn’t make any difference. I showed them how to make up beds and we set it up in this huge dining room; it had the nurses’ station over here. We thought that we were going to have to man that during the trip, the medics of the 78th Fighter Group, but it so happened that a hospital group came aboard. So, immediately we turned it over to them to operate which I was so glad for.

I could just imagine when that ship was up and down like that I don’t know what happened back there in the hospital.

Getting back to that we arrived at Goxhill December 1 of 1942.

Part Two to follow.

Part Two: Deployment and Action

Noble B. Vining: It (Goxhill Aerodrome) was spread out over quite a ways; a train line went through there. It was that big it had two train stops there.

We were there and our P-38’s and getting ready to go into action.

In North Africa they needed some air cover desperately. They transferred all of our P-38’s and all of our fighter pilots to North Africa. And when they left they did a fly-by single file, over a hundred fighter planes, when they left for North Africa.

It so happened that there weren’t enough pilots to fly all the planes down so some of them came back to get the rest of the planes. And they told us that when they got to North Africa they didn’t even have time to go to the bathroom. They armed those planes every way in and went into action right away in North Africa.

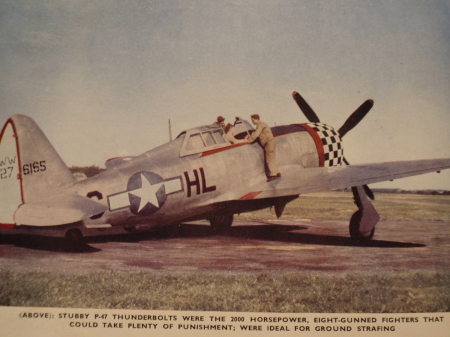

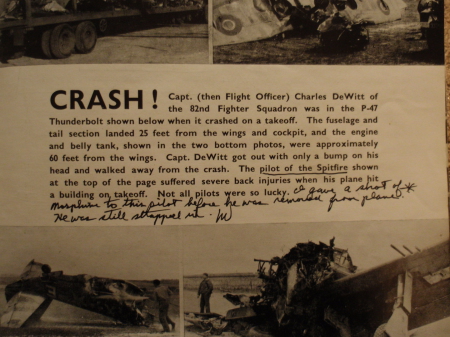

They flew in P-47’s, which were air-cooled radial engines, single-engine plane known as the Thunderbolt. We quickly retooled and retrained the men on those engines and we moved further down south.

VFW Post 1697: When you’re talking about training the men?

Noble B. Vining: The ground crew.

VFW Post 1697: Maintenance?

Noble B. Vining: Well, they were the crew chiefs. See, every plane had a ground crew to keep up the engines; they had to learn this new engine.

We moved down after that, we had the Thunderbolts, and we moved down to this location called Duxford Aerodrome which is ten miles south of Cambridge, England, in East Anglia, where a lot of the bases were because that was nearer (continental) Europe, you know.

We occupied the permanent RAF [Royal Air Force] aerodome, Duxford was, they had it in World War One. It was steam heated, the barracks were, two floors, and they had showers, I mean it was nice, those were. Well, a row went between the barracks and everything else with the hangars on the other side.

We were there and a few days before we did our first mission the old RAF Eagle group—you know, the Americans did join the RAF and they formed the Eagle Squadron, I think—they had changed to American Air Forces under the 8th Air Force (Fighter Command), they went into action and I think in less than a week later we flew the first mission, a full American (fighter) group there. Well, we were there, that was in, I think it was in May.

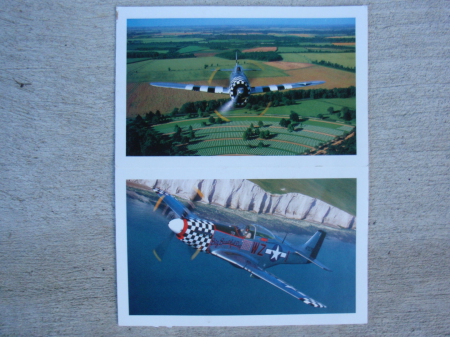

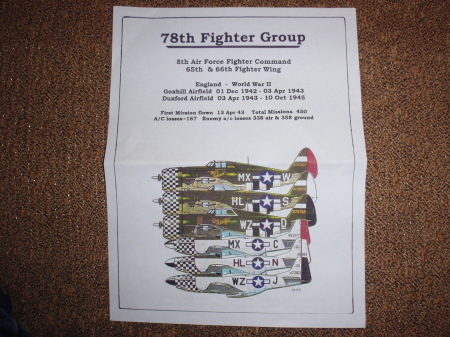

What I’ve got here is what’s called “The Duxford Diary,” and it tells the whole story of everything in here. I haven’t even read it recently. In fact, I’m not sure I’ve ever read all of it. But, anyway, it tells all these things. See that plane, WZ? That’s the squadron I was in, the 84th Squadron, was WZ. You see how it’s landing there?

VFW Post 1697: Would you call it Whiskey Zulu?

Noble B. Vining: I don’t know what they called it. But anyway, see how he lands?

VFW Post 1697: Yeah.

Noble B. Vining: He’s the only one, Colonel Landis, that landed that way. He flew into the ground; the others came in and squatted down and let the tail end drop down, you know. He’d fly in with (all) the wheels touching the ground. He really was something. Everybody would look for him to come back, and he was the commanding officer of the Group, but he flew out of the Squadron. So that WZ plane was called the “Big Beautiful Doll” and it’s been known, you’ve seen pictures, and I’ve got a plane in there with WZ on it.

VFW Post 1697: Remind me what plane that was.

Noble B. Vining: That was the P-51 Mustang. The P-47 Thunderbolt’s the one we had up until ’45. In ’45, the latter part of ’45, that’s when we lost the Thunderbolts. We had the P-47 Thunderbolt that we did the Invasion with, but in ’45, later on, we got the P-51, that’s the Mustang. That’s the one that got so popular, you know, before the War was over, the Mustangs.

As far as this shows here, a little bit of the history. Oh, this is another thing.

The last mission that we flew they flew into Berlin and on the way back the RAF was bombing Berchtesgaden, where Hitler’s home hideout and everything. The weather was so bad in England that their RAF fighters could not take off and so they had no escort. So they got in touch with our Group to form escort for them, so instead of coming on back straight from the mission they flew over Berchtesgaden to cover that mission. But by that time they were using up the fuel so they landed all around different parts of Europe there, you see it was already occupied, to refuel. Well, some of those guys just took advantage and stayed over a day or so maybe. Finally, they all got back, but that was the last mission of the War. The War was over right after that, in May 1945.

VFW Post 1697: Now you yourself, I mean, you stayed on base?

Noble B. Vining: Oh well, I’ll explain that. You see, with the Fighter Group, Fighter Squadron, the fighter planes there was only one man, I mean they really were in the War. They aimed their guns with the plane and also there were cameras on there that would take pictures when they’d shoot, shot their guns and they could either arm with bombs, some little wing bombs, or they would have regular wing guns, and everything. And so, that way, there had to be for every plane there was a crew and a crew chief, and they were the ones who were on the ground all the time. They stayed with the plane. See, we were on alert all the time; we never knew when they would take off so there was somebody always out there ready to start the plane.

And then there was a service group there that took care of a lot of other things. And our Squadron itself had about 300 men in it, but you see, there were only about thirty-five pilots. But we had to support all this. Each squadron had their own dispensary and took care of any sickness, shots, examinations, crash records, anything that came along.

One thing that happened: I happened to be in charge of the quarters of the dispensary. We were all in the same building but we had three different dispensaries and I was in charge that day and a bomber, B-17, visited the base and when they were taking off they hit the wind sock and there were thirteen men on the plane and they headed over and crashed into the wing of a barracks with that plane. Of course it exploded and there was fire that killed all the thirteen men that were on the plane. There was one man in the barracks. The barracks ten minutes before that had been full of men. It was at noon and they’d gone back to work. So if it had been ten minutes earlier! But anyway, it fell my duty, because I was in charge of quarters, what they did was bring the pieces of the men, the bodies over to our dispensary which had a morgue. We had a morgue there. And so they brought it over and they kept bringing everything they could find and laid it out on the floor of the morgue, all these pieces.

Well, the next morning it fell my duty, because I was in charge of quarters that time, to help identify these bodies. And the dentist, he’d gotten the dental records for these men, they knew who they were because they knew who was on the plane. So he had the dental records. So we went down there that morning. And man, it was terrible, the stench. You can imagine just bodies blown apart, feces, and oh, it was awful. But anyway, we went about, he was identifying what he could from the dental work and I was piecing things together, finding dog tags, and I remember picking up the head, shoulders and arms of somebody. And I walked around trying to find where it would match, you know, looking here and there trying to match it. But it was hard when you think of it.

Well, anyway, another thing that happened while we were there. We had taken our first bodies to south of London to a cemetery, it was part English and part American. But the rumor was they were starting a new cemetery which they did which was about ten miles from us out from Cambridge. Before it was over with I think there were 20,000 buried there, beautiful spot. When you go there it’s so sad, when you look at the markers there, you know, twenty, twenty-one, twenty-two years old, all those young men.

Well, anyway, the War was over and I came back and was discharged October 14, four years later from the time I went in in the same place.

You see, I did do this. I flew once with, they had a Beechcraft, something there they used just to fly around. I went one time flying with them on that after the War was over, after VE [Victory in Europe] Day. They flew simulated bombing missions over and what they did was to let the ground crew register and they drew their numbers, and if your number was lucky you got to go on one of these simulated missions. Well, I was fortunate and they only took just what the crew was like on the B-17, you see, and I happened to get the waist bomber's position on that plane. Well, the fuselage, you see, comes down, it’s round and when I stood facing that window it was way over here. The fuselage, you see, came back when I was standing. So, in order to see I had to lean way over like this to look down to see the ground. Well, that gunner, he never saw the ground when he was up there. I mean, he was looking out the plane to shoot at, he was looking for planes, the fighters were up there and they were ready to shoot down any German planes, so the poor waist gunner, and the guy in the bottom of that turret down there, oh man, it must have been awful to be in that. But anyway, I did go on a simulated mission. The guys always called me “doc,” it was my nickname and I got seasick, no, airsick, they were worried about me up there, you know, but it was only when we went on across the (English) Channel that we [had it] pretty rough.

VFW Post 1697: So where were you released from the Service?

Noble B. Vining: Well, I came back out from Fort McPherson in Atlanta, same place I went in, and there were guys sitting there that had been drafted and were still ready to go. I do remember, though, after Pearl Harbor, after (President) Roosevelt declared war, orders went out. When we got there the men that first had been in and served their year, it was supposed to be one year, and they had their things and were leaving, they were just razzing us and said, “Well, you guys do it now, we’ve done ours,” and you know, it wasn’t just a couple weeks later that everybody was returned to their original outfit, so here they come back. We razzed them and said, “You’ll be in an extra year; you’ll be in as long as we are.”

Well yeah, okay, I think that pretty well sums it up.

VFW Post 1697: Thank you very much, Mr. Vining.

Noble B. Vining: I forgot to mention that when D-Day took place our Group had already been in action a year or more, so it was old hat to fly missions. I happened to get a pass and was going back on the Base on June 5. I was going back that night. The train station was about a mile or so away from the Base and those of us who had connections in Cambridge would go in if we could and take our bicycles. We’d ride in and then we’d come back on the train and put our bicycles on the train. Well, that night those of who had passes were all coming in down the road; we occupied the whole road our bicycles did. Before we got to the entrance to the Base the road was closed to traffic. Before that civilian traffic, you see, went back and forth, but it was closed to traffic. Well, that didn’t stop us. But as we came we saw that they were painting these black and white stripes on the fuselage and wings of the planes. That night in the the entire RAF and US Air Force, every plane had uniform stripes painted on the fuselage and on the wings whatever kind of plane it was, the reason being that when all these planes went into action over troops they needed to know who their friends were. Any plane with the stripes was a friend; the rest they were free to shoot down. So that was the part we played. I say “we”; I’m talking about our pilots. They took off before daylight that morning and all during the day we had a squadron of planes over the Invasion, relaying back and forth. See, we had the three squadrons and each one would [in turn], one would be on the way back and have to refuel, and rearm and so forth, so it kept a circuit there. And always there was a squadron over the D-Day (Invasion).

VFW Post 1697: Do you happen to know which beaches they were over?

Noble B. Vining: I don’t know for sure which ones they were. They had drafted some of the teams; like our flight surgeon went and he was on one of the landing crafts that went in, and then we had some of the medics. I didn’t go; I was the sergeant in charge of the detachment. I don’t think we suffered any losses that day.

I just wanted to add that in about our part in D-Day. It was a routine thing for that Group to fly missions. Those pilots, remember that they faced their opponent in these dog fights. You know, they were trying to shoot each other down.

Today it’s a different story. We got missiles and don’t see what they’re shooting at.

VFW Post 1697: Radar takes care of that.

Noble B. Vining: Yeah. So, it was something. Well, in all we lost, I’m trying to see how many there were, I think 110 names here.

VFW Post 1697: These are all pilots?

Noble B. Vining: Yeah, these are all the pilots or some relation, the ones we lost during the War, who died in their Country’s service. See, there are pages here of names of our Group who were lost. “Missing in action” there. And this is a roster here; my name will be in there. It’s got a lot of information in here. There’s the pictures, cemetery there.

VFW Post 1697: Right. I might take some pictures of that. So that’s going to conclude this part [of our interview]?

Noble B. Vining: I think so.

VFW Post 1697: Thank you. Thank you, Mr. Vining.

Above: REPUBLIC P-47D-25-RE "THUNDERBOLT" IN THE COLORS OF THE 82ND SQUADRON, 78TH FIGHTER GROUP, EIGHTH AIR FORCE, BASED AT DUXFORD AIRFIELD IN 1944. PHOTOGRAPHED OVER THE CAMBRIDGE AMERICAN CEMETERY AT MADINGLEY, ENGLAND ON JULY 7, 2000. OWNED BY THE FIGHTER COLLECTION, BASED AT THE IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM, DUXFORD AIRFIELD, PILOT, STUART GOLDSPINK. PHOTOGRAPH BY PHILIP MAKANNA.

More: The P-47 is shown with the Invasion Stripes on the fuselage and wings. They were painted on all Allied Planes the night before the Invasion, enabling the Invasion forces to know that they were not enemy planes. They were also the first Group to be equipped with the P-38 Lightning and were operational with it on the [American] west coast with three squadrons. Just ready to fly their first mission in the 8th Air Force in England, they were transferred to North Africa with all the Pilots. The just-put-into-service P-47s and new pilots replaced them. A quick retooling and training of the ground crews took place. --NBV

Above: "BIG BEAUTIFUL DOLL", REPRESENTING THE NORTH AMERICAN P-51D "MUSTANG" FLOWN BY COLONEL JOHN D. LANDERS, COMMANDING OFFICER OF THE 78TH FIGHTER GROUP, DUXFORD, IN EARLY 1945. PHOTOGRAPHED OVER ENGLAND'S SOUTHERN CLIFFS ON JULY 3, 2001. OWNED AND FLOWN BY ROBERT W. DAVIES, MBE. PHOTOGRAPHED BY PHILIP MAKANNA.

More: The P-51 Mustang is shown. It was put into use after the Invasion so you will not see one with Invasion Stripes. This plane was from the 84th Fighter Squadron and used the WZ call letters. It so happened that the 78th Group Commander flew out of that squadron and he had a distinct style of landing. His “Big Beautiful Doll” has been used in most P-51 photos and plates, etc. It was my privilege to be in charge of the medical detachment and the Flight Surgeonʼs Assistant in the 84th. --NBV

Above: NORTH AMERICAN P-51D MUSTANG 44-63864 "TWILIGHT TEAR" WAS THE PERSONAL AIRCRAFT OF 1LT HUBERT 'BILL' DAVIS, 83rd FS/78th FG, BASED AT DUXFORD IN MARCH OF 1945. IT IS SHOWN HERE IN FORMATION WITH A REPUBLIC P-47D THUNDERBOLT REPRESENTING "NO GUTS-NO GLORY", THE PERSONAL AIRCRAFT OF LT COL BEN MAYO, CO OF THE 82nd FS/78th FG, BASED AT DUXFORD IN 1944. PHOTOGRAPHED OVER DUXFORD, ENGLAND, ON JULY 10, 2003 BY PHILIP MAKANNA. BOTH AIRCRAFT ARE OPERATED BY THE DUXFORD-BASED FIGHTER COLLECTION. PILOTS: STEPHEN GREY, P-51 MUSTANG AND STEVE HINTON, P-47 THUNDERBOLT.

More: Here we see planes from the 82nd and 83rd squadrons with their call letters. The Invasion Stripes are more visible here. The Thunder Bolts were replaced by squadrons of the P-51s, the last being the 84th changeover in January of 1945. --NBV

Above: THE UK'S ONLY AIRWORTHY B-17G "FLYING FORTRESS", SALLY B, FLAGSHIP OF THE AMERICAN AIR MUSEUM IN BRITAIN AND REPRESENTING THE MEMPHIS BELLE OF THE 91ST BOMBARDMENT GROUP, UNITED STATES EIGHTH AIR FORCE, ESCORTED BY A SPITFIRE F MK. VB. PHOTOGRAPHED OVER DUXFORD, ENGLAND, ON JULY 11, 2002, BY PHILIP MAKANNA. DUXFORD-BASED SALLY B IS OPERATED BY B-17 PRESERVATION LTD AND SUPPORTED BY THE B-17 CHARITABLE TRUST (REGISTERED CHARITY NO. 1079007). PILOTS: ANDREW DIXON AND JIM JEWELL. THE SPITFIRE IS OWNED BY THE HISTORIC AIRCRAFT COLLECTION LTD. PILOT: CHARLIE BROWN.

More: The B-17 Flying Fortress was the plane that did daylight raids with sometimes as many as a thousand planes in the sky at one time. The B-17 had nose and tail gunners, top and bottom turret gunners and waist gunners on each side. The pilot, co-pilot, navigator, and engineer made up the crew. There was little defense from the ground fire. There were always some who did not return. Our fighters would leave after the bombers and catch up with them when they got in range of German fighters. Our planes had cameras that took pictures every time the guns were fired. These were developed immediately on return to see what had happened. --NBV

BILL NUTT

EDITED TRANSCRIPT of Bill Nutt INTERVIEW on June 19, 2013

VFW Post 1697: This is Lew Szerecz from Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 1697 speaking with one of our Veterans, COMRADE Bill Nutt. I’m interviewing him about his experiences on D-Day, 1944. What ship were you on?

Bill Nutt: I was on the USS Ackernar (AKA-53). It was a lead ship. [The supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, General] Eisenhower chose us as a lead ship to lead the invasion and we had two generals on board. They were in the War Room with the maps and I was sent down with a message and I opened the door. I saw the two generals at the foot of the table and on the table were little wooden tanks and men and on either side of the table were about four people on each side with ear phones on, taking messages from the Beach and moving little wooden tanks and men around so they would know exactly where they were. And later that same day there was a ship stranded on the beach.

LS: What was the date of the invasion?

Bill Nutt: It was June 6. Later that day I was asked because there was a ship stranded on the beach the sea-going tug couldn’t get any close to enough, so I got the cable from the sea-going tug and carried it into this ship, and as we were putting the cable on the ship we heard a roar and we looked up and saw a Black man in a duck [DUKW: a six-wheel drive amphibious truck]. A duck goes in the water and on land, and so he was coming back from the front wide open, and as he hit the beach he hit a mine that had drifted up on the beach, one of them big mines that sink ships. Anyway, he hit that thing and he just flat disappeared from view. I mean, nothing came down.

LS: How did you actually get to the beach close enough to be able to attach that cable? What kind of vessel were you on?

Bill Nutt: Oh, I’m on one of those tank lighters. It only drew three feet of water, it’s shallow. Landing craft are built that way so they can get right up on the beach. It was an LCM, though; it was a tank lighter.

LS: That’s what you were captaining.

Bill Nutt: Yeah.

LS: Was that the only time that you were in a landing craft?

Bill Nutt: Oh, no.

LS: I mean that day, I mean.

Bill Nutt: Oh, that day? Yeah, I think that day was the only time I was in a landing craft after that trip.

LS: How many crew were there on the landing craft with you?

Bill Nutt: I had a four man crew.

LS: But you were the captain of it.

Bill Nutt: Oh, yeah, in name, but not in rank. At the time I was a coxswain.

LS: What beach was this?

Bill Nutt: Omaha Beach. There were three-thousand killed at Normandy on Omaha Beach, but they had several beaches. And it totaled to about forty-three-thousand killed for that single day.

LS: How long were you near Omaha Beach? How long did you participate in the invasion?

Bill Nutt: Let’s see. Oh, we were there for six days until we got a beach head. Once they got the beach head then we went back for another load of whatever they wanted. They had barges and all sorts of things, maybe the stuff that was to be transported over to the Rhine River. We had a few of the boys that had these tank lighters and the personnel boats run by tractor-trailers over to the Rhine to ferry the vehicles and the personnel across the Rhine.

LS: Now that first day, on D-Day, you were running a tank lighter to get to attach the cable to that stranded ship. What’s the Navy designation for one of those boats?

Bill Nutt: This here was an LCM, landing craft mechanized.

LS: That’s what you were running. Now, did you ferry other items to the beach during those six days?

Bill Nutt: No.

LS: But that was the only time that you were actually approaching shore in order to get that job done?

Bill Nutt: Right.

LS: The rest of the days you were on board ship?

Bill Nutt: Yeah. I did later take a trip in, just looking. We walked a ways up in. One of the boys saw a German helmet with a bullet hole, he wasn’t there. But anyway, he took some sand and scrubbed out the brains. One of the captured Germans, they asked him, where the best of the troops were. He said, they are all dead in Russia, all dead in Russia.

LS: Do you want to say anything else about your Navy service? Now I understand that in 1945 you participated in the invasion of Okinawa in the Pacific?

Bill Nutt: Yeah, but we had another one in southern France. We carried a group of French Moroccan soldiers. These guys were all six or seven foot tall and the guy that was in charge of them, he was about five foot, a Frenchman from France. All they carried was big old swords. The ship brought them over as close as they could get, then I with my tank lighter, I carried them in. Just before we landed a group of B-25 bombers out of North Africa flew over. They were supposed to hit the beach but they botched, the bombs fell short of the beach. We were out there circling around, waiting for the flag to go in. The bombs landed all around us. I heard about sixty years later at a reunion that one of our boys did get killed. That was around August, the early part of August, 1944.

LS: Did you stay on the Ackernar all the way to the Pacific?

Bill Nutt: Oh, yes. From France we came back to have some work done on the ship, back to Norfolk Navy Yard. They used to have a lookout station on top of the ship and one of my duties was to climb up there, crossing the Atlantic. And sometimes you’d be upside down looking out over the ocean, then on the other side you’d be the other way because the ship was rolling in the waves. I think I left my fingerprints in them steel rungs. I tell, I hung on, wind blowing, and all that, you know. A crow’s nest on top of the mast was like a big can: once you get inside, used binoculars to scan the horizon. You could see eleven-and-a-half miles, I think it is. Once we changed to the Pacific we didn’t have to do that because by then we had radar.

LS: So, did you go through the Panama Canal?

Bill Nutt: Oh, yes. There was a young fellow down there and his brother. His brother was in the Army and he was, of course, in the Navy. And they had a weeping party. They thought something’s going to happen, and it did. The boy got killed.

LS: Now, he was a shipmate?

Bill Nutt: Yeah. We had a suicide plane hit the ship in Okinawa. I wasn’t on it. I was sitting on a load of gasoline on the beach in Okinawa. How it happened was they called it standing out, getting away from the group of ships. The water in the Pacific is so fluorescent, it’s like a neon sign. This plane was one of our own planes that was sold to the Japanese as a crop duster, double double wing. And they had a five-thousand pound bomb lashed to the rigging and so the water being so fluorescent, I mean, it’s just like a neon sign, this guy, this suicide plane followed it out, circled around, and tried to hit the superstructure. If it had’ve, it would have sunk the ship. But it landed in the rigging and the bomb slid over the side and went off. And when it did, it killed five boys on lookout in the gun tops and around. The bomb blast was strong enough so it blew back shrapnel through hundreds of holes of the side. What they did was, quick thinking on the officers’ part, they rolled the ship on its side, called the carpenters, and they came up and plugged all the holes.

LS: How did they roll the ship on its side?

Bill Nutt: Well, they took on ballast, ocean water that would make the ship list, so that they could get over there and plug the holes. They had carpenters come up.

LS: Yeah, but what did they use to plug the holes with.

Bill Nutt: Wood. Carpenters use wood. You don’t take parts off of the ship and plug a hole. Although, when I dropped my tank off there in Okinawa I hit a reef that split the hull, but I had a ballast tank, and the ballast tank filled up and I went back to the ship lopsided and they pulled me up and drained the water out, welded a patch over it and put me back down and they loaded me with the gasoline. I had a whole boat load of five gallon cans of gasoline and I sat on the beach while they were steamed up there and got hit.

LS: But in the meantime there was still a battle going on, wasn’t there?

Bill Nutt: Well, let’s see. It was the biggest fireworks I’ve ever seen, like a Fourth of July, but the Japanese weren’t dumb. They were eight miles inland, but we hit the beach. [We] had those rockets stacked, they were first, and peppered the beach with that, then the next size ship, they did their thing. Then they kept getting bigger and bigger and I was sitting beside the Big M, the Battleship Missouri when she let loose her broadside and I saw the sailors on the deck close to them stand on their toes and open their mouths so it wouldn’t blow their ear drums out. And they could only shoot one way. They could only shoot a broadside because of the recoil, and the ship just rolled over on its side, you know not all the way, but I mean, rolled back, and I think it was about a thousand pound projectile out of each barrel. They had four barrels to the turret and four turrets, I mean there were. Man. And every, every twenty minutes WHOOM again.

LS: So, in other words, you were there just as the landing was about to start.

Bill Nutt: Oh, yeah.

LS: So, how long were you around or in Okinawa?

Bill Nutt: How long? I think we were there I don’t know how many days but eighteen days, and nineteen days. I know how to find out. I got the minutes that tells us where we were every second.

LS: Now, from Okinawa where did you go on the USS Ackernar?

Bill Nutt: We went back for repair. We went back to San Francisco.

LS: Did you go under the Golden Gate?

Bill Nutt: Oh, yes! We’ve been under it several times. And they sent us on a thirty day leave and—

LS: So, but wait a minute. When was the war over, when you were on leave?

Bill Nutt: Oh, no. We went back and there was one fellow that didn’t go back. He said he’d rather be a live coward than a dead hero and he spent three years in a state penitentiary for not going back. And I was, we were sitting in Pearl Harbor and I had the maps, studying these maps, we were going to invade Japan when at night a voice in a movie--[U.S. President] Harry Truman--they came on then and announced that the war was over because they dropped the [atom] bomb. It saved millions on both sides. When I was in Florida there’s a guy who said, this soldier said he was scheduled for the seventh wave and they figured the first eight or ten waves would be total loss because we had the little boats to carry them in and it would have been many waves in the Navy that lost these little landing craft. So the bomb saved millions on both sides.

LS: Now, how much longer were you in the Navy?

Bill Nutt: Well, I was in ’46. (See, the war was over in ’45.) It was January, actually. When we came back we didn’t do much. We just sat around until they discharged us. Well, I say the Lord blessed me.

RAYMOND C. BROWN

A close call for Pfc Raymond C. Brown during World War II

I was thinking, “Why should I be afraid? I know I am in the Lord's hands. After the miracle on my first jump, it doesn't make any difference because it is up to the Lord and I am trusting Him to do what is right for me.”

A couple of days later we met some strong resistance and began to dig in. In combat whenever you stop you start digging. Bob and I were digging our foxhole. It was coming along nicely when suddenly someone shouted, “The mail is in!”

I always marveled about the mail. In the strangest places and at the strangest times it would arrive. Here we were in combat and we got mail. The German artillery was lobbing shells in on us, the explosions sometimes fairly close.

“Go get the mail,” I told Bob. “I'll keep digging.”

“No way! I am not getting out of this hole, you go get the mail!” he said.

I said, “Okay. I'll get it.” With that, I climbed out of the hole and started walking back toward where the mail was. Suddenly everything went black. The next thing I knew, I could hear voices a long way off. They seemed to be getting closer and closer. Then they were next to me.

One voice asked, “Is that guy dead?”

Another voice answered, “I don't know.”

I opened my eyes, and I was in a big snow bank with blood. I had a terrible headache with ringing in my ears. I said, “I am alive. I have to get the mail.”

They took me to a medic, who pulled out some shrapnel and bandaged me up. As I had walked away from Bob and the foxhole, a shell had come in and exploded. The explosion threw me about thirty feet into a large snow bank, and I had been unconscious for over three hours when they found me.

“What happened to Bob?” I asked.

They replied, “You don't need to worry about Bob.”

Later I learned that the shell had landed square on top of our foxhole, and Bob had been blown into small pieces. There was nothing left. I'd lost another friend. And I had lost my equipment again. My ears were ringing for a week or more. Once again all I could do was say “Thank you Lord!” There wasn't any mail for me.

****

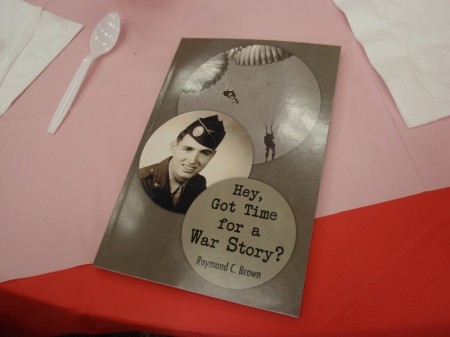

Hey, Got Time for a War Story?

Raymond C. Brown

Pages 86-87

As we moved forward, resistance stiffened and we were battling again. We stayed there a few days to consolidate our positions, got re-supplied with ammo and food, etc. They brought up the artillery, and we dug in. The Germans had a defense line where they were dug in with foxholes, bunkers, mines, and some barb wire in front of them. While we were waiting to attack, Fox Company had a mission.

We had spotted a stone barn that appeared to be German headquarters. Our mission was to attack the stone barn, capture the officers, and bring them back, for the Germans did not do well when they lost their leaders. We set our watches. The artillery would have a rolling barrage, landing shells ahead of us as we moved up. With nightfall came the hour to leave. The artillery started their rolling barrage, and shells were coming in. Just ahead of us, some guys moved forward, cut the barb wire, checked for mines, and put tape down. We walked inside of the tape path. Fox Company was going to attack a small town as a diversionary tactic while a small group of which I was a member was going to attack the barn.

Fox moved on, got behind the German lines, and the company moved south. Our group of ten slipped away, moving east. Each had a pack loaded with the always versatile Composition C, a deadly high explosive which looked like putty and could be shaped or stuck to something. We liked it.

We walked very quietly: no talking, no sound of any kind. Later we heard the noise of our company attacking the town even as our artillery was lobbing shells on the other side of the barn. Ahead the barn loomed out of the darkness. We stopped and began to whisper about our plans. I was standing awkwardly with my feet wide apart and didn’t know why. Suddenly a machine gun came out between my legs and started to fire. I flipped over backward and hit the ground. Now I knew why my feet were so wide apart. I was standing over a hole that led to a bunker. The other soldiers were standing on either side of me, so no one was hit, for the machine gun was firing straight ahead. A couple of the guys rolled grenades into the hole. And we moved off. After they exploded it there was no more machine gun or its crew.

I was still on my back. The guys ran over to me, thinking that I had been hit because of the way I had fallen backward into the snow.

“R.C., where are you hit?” someone asked. “I am fine. You guys, ok?” I replied. We were all unharmed and went to the end of the barn’s wall near us only to find there was no opening in the stone wall. Now back to the plan. We took off our packs, saving two for later, got out the Composition C. We put it on the wall, shaped it, put in the blasting cap, and unrolled a roll of primer cord. We planned to blow a hole in the wall, rush in to capture the prisoners, and destroy the German headquarters. We lit the fuse and lay down on the ground. A tremendous explosion shook the ground so that it felt like we were lifted into the air. Through lots of smoke and dirt, we ran to the wall to go through the opening we had created, but when we got there, the wall was still intact! I guess we hadn’t shaped the Composition C right. Still, the tremendous explosion brought the Germans running outside without their weapons, so we rounded them up. Two guys ran inside with their packs of Composition C, blew up the barn and set it on fire.

We checked our watches, it was time to go. The artillery was starting the rolling barrage to cover our retreat. We had to hurry or the shells would be landing on us. We moved along with our prisoners, meeting up with the rest of Fox Company returning from their attack on the town. The artillery kept putting shells behind us. We found the barbwire and walked between the tapes. Mission completed. We had the prisoners, had destroyed their headquarters and with no casualties.